|

| Image Credit: guardian.co.uk |

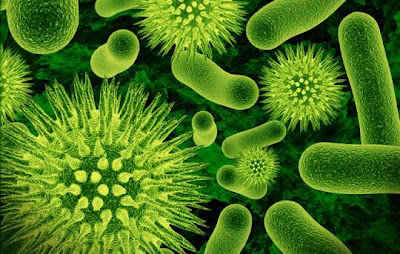

Generic drugs should be any health worker’s favorite tools. Unfortunately, the world of medical aid missions is not resistant to the politics of drug pricing and distribution. Medical R&D practices have multiplied the world over, giving rise to affordable science. From the primordial knowledge soup of advanced medical technologies, no exclusive R&D results arise.

Stiff market competition among purveyors of high-demand drugs was the status quo until the advent of patents. Even then, emerging economies, such as India, are persisting with generic drugs production, naturally rankling huge pharmaceuticals. India offers some of the cheapest medicines in the world against cancer, tuberculosis, and AIDS. Its homegrown pharmaceutical industries were collectively worth USD 11 billion, and according to Le Monde diplomatique, it is set to inflate to USD 30 billion by 2020.

|

| Image Credit: echoofindia.com |

The medical profession isn’t homogeneous in its hawkishness, and humanitarian doctors have stepped up to the plate in the promotion of generic drugs. For instance, New York-based nephrologist Paul Frymoyer and Deane Marchbein of Doctors Without Borders, whose experience in giving medical aid in African missions opens to them the realities of epidemics and pandemics, could find recourse in generic drugs to push aid distribution far.

|

| Image Credit: outlookindia.com |

The reality is that the pharmaceutical industry is divided by its quest for profits and mission to equip the world with advanced medical solutions. India’s local, healthier pharmaceutical competitive market has evened out this contradiction, yet it remains at the behest of international trade agreements. The European Union, headed by President Juan Manuel Barroso, denounced India’s cheap drug exports, and resorted to supply seizures in what the World Health Organization considered as an abuse of counterfeit laws.

As a prominent nephrologist, Dr. Paul Frymoyer is especially concerned about new medical trends. Visit this Facebook page for more information.